By Amanda Sharma

He’s two. He plays with a copy of Goodnight Moon in the car, practicing turning the pages and finding the mouse in the pictures. The symbols on the pages mean nothing to him, yet, but someday he will make sense of them. Just two years ago, he was still inside of me, listening to my voice and not comprehending the words. Now he points at the page with a chubby finger: “Night-night moon! Where’s mouse?” He’ll make sense of the written word the same way he made sense of the spoken word. By soaking it up from the big people around him.

His sister is seven. She looks up from a copy of The Neverending Story that rests in her lap, and helps him find the mouse on the page.

“How long till we’re there, Mamma?”

Reading is as useful as talking, if the world around you is full of words.

I point out the next sign. More symbols. Reading is as useful as talking, if the world around you is full of words. I try to make sure my children’s world is full of words. I help them make sense of those words when they ask. That’s my curriculum.

It’s the same one my mother followed, back when “Unschooling” was barely a term. I learned to read leaning up against the soft cushion of her arm, scanning the words as she read them. I don’t remember many lessons. I do remember hours upon hours of adventuring through stories together. She read whether we were sitting still or not. She read as we rolled around on the floor, and hung upside-down on the sofa.

I learned to write because I had stories bursting out of my veins, and parents who took joy in them. The first time I decided I wanted to be published, I was nine. Instead of treating me like a child, as adults are prone to doing, she helped me write out an admission letter and send it off.

My daughter presses her nose against the window. She’s always been my early riser. When she was two I used to set her up a little “nest” next to the heater, with pillows and books and a cup of cereal, so that when she woke early she could sit quietly and look at the pictures. She’d make up the stories as she turned the pages.

At age four she enjoyed phonics workbooks, occassionally. Words were fascinating to her, and she desperately wanted to puzzle them out.

Learning by choice means using any tool you choose. Provide lots of tools. Let kids pick and choose the ones that work for them.

Never listen to someone who says an Unschooler can’t use a workbook. Learning by choice means using any tool you choose. Provide lots of tools. Let kids pick and choose the ones that work for them. Unschooling isn’t about “can’t”. About what you don’t do. It’s about following curiousity wherever it leads.

Make curiosity your curriculum.

And if the workbook doesn’t work, if the child doesn’t choose it, if it’s like a wet towel on their curiosity instead of fanning the flame…then toss it. Leave it on the shelf. Stick it in the burn bin. A tool is only helpful if it works.

Mostly she just looked at books alot. We used to joke that you could find her by the trail of books she left behind her. And I read to her a lot. I remember when suddenly around age three she made the connection that the symbols on the page were what I was deriving the story from, and wanting me to show her what each word said.

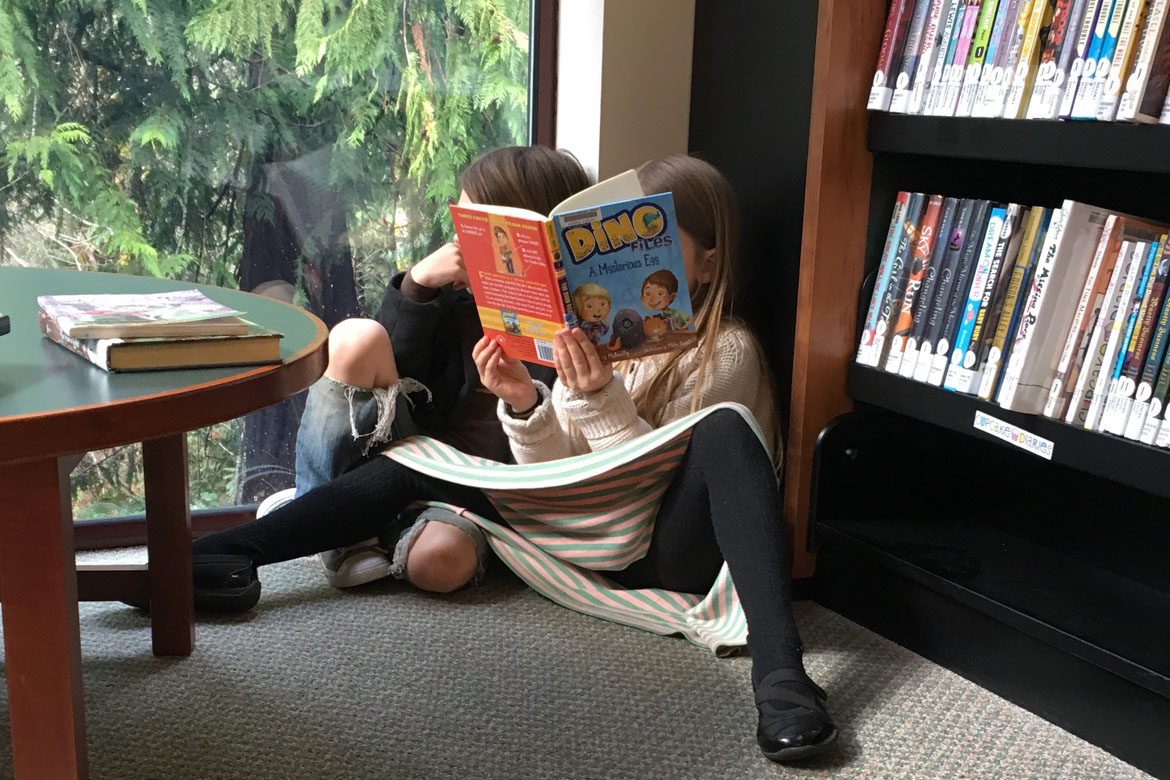

At age five her Farmor came to visit from Stockholm and brought her an abridged copy of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Nights Dream. The pictures of dancing faeries sent her over the edge. For weeks she carried that book everywhere she went, reading paragraphs over and over and over until she had them memorized. By the time she’d puzzled out that book, she could officially read. Her own strong desire to know the story had taken her from sounding out short, three letter words, to reading Shakespeare. Since then, she has gobbled up books like candy, bringing stacks home from the library every week.