By Tracy Cassels

Some of you aren’t there yet, some of you are in the midst of this, and some have come through the other side with a whole new set of skills and experiences: that moment when your child refuses your comfort when they are upset. That moment they are upset and instead of coming towards you, they are getting away. To be clear, this isn’t about infants, for if they are arching away when upset, they are likely picking up on your distress or are in pain and trying to move around to relieve it. No, this is about your toddler or perhaps preschooler.

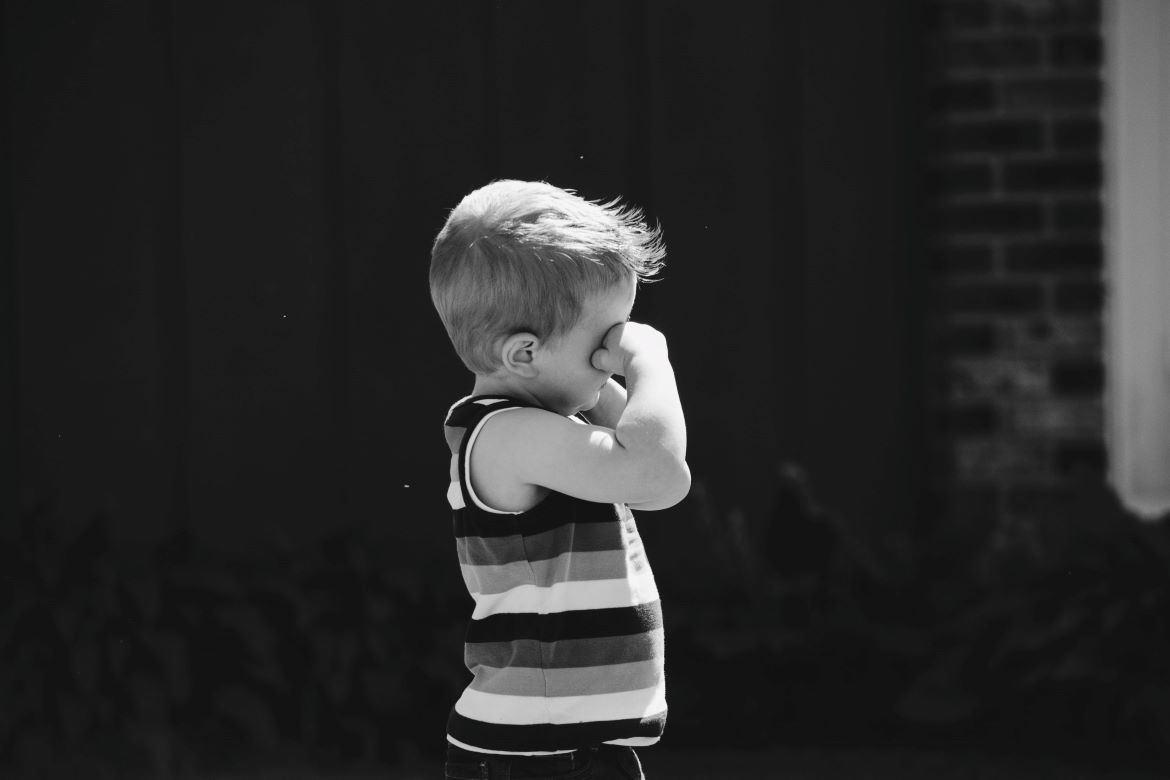

The child who would get upset, frustrated, angry, or hurt and would cuddle in your arms until the feeling passed. You could feel like you could ease all the hurt in the world so long as he could just snuggle in while you held him tight and stroked his hair or face or just simply sat with him. No longer. Suddenly, you find yourself reaching for your child in his moment of upset and instead of turning towards you, he turns away. In that moment, you feel the air leave the room and the panic set in.

What have I done? Does he not feel attached to me anymore? Have I not been there enough lately?

Every negative thought you have of yourself as a parent is rushing forward like water after a dam breaks. You look at this child – this love of your life – who is in pain and struggling and you so want to help, but she won’t let you and of course the only reason that comes to mind is that you have failed somehow. You have done something wrong, so wrong that she refuses to allow herself to feel better by being with you. You may try to reach out for her with force, knowing that if you could just get her to your arms, everything would be okay.

But she refuses.

***

Too many parents find themselves in this situation. They feel helpless and as if they have done something “wrong” with their child. What is missing from the discussion, and why this discussion is based solely with toddlers and up and not younger children, is that this is very normal and actually quite healthy. Not all children will do this (after all, outside of normal bodily functions, there’s almost nothing universal about how children express themselves), so don’t panic if your child doesn’t, but for those going through this stage, it’s essential to better understand it and how to cope.

What is going on?

In short, your child is trying out self-soothing. We’ve been so misled to believe that children master this skill early in infancy that we ignore that that is a far cry from what is biologically normal or even possible. The first real stage of emotion regulation that infants show is seeking out a caregiver for assistance in their ability to soothe themselves (see here for a review), but as they develop, they learn new skills that help them self-soothe. Of course, to see how these work, a child needs to practise them. Without practice, he doesn’t know how it will work or even if it will work.

What age does this start?

The age will be highly variable depending on a variety of factors. Of course child temperament will be a huge factor, with many highly sensitive children likely demonstrating this later than their less sensitive peers.

Research on children who are highly sensitive shows that they seem to require much more responsive parenting in order to thrive (see here) and this can include longer bouts of needing the modeling of responsiveness before they can attempt to self-soothe on their own.

Other factors that may influence when this change occurs include: the amount of time spent away from the attached caregiver, such as when a child enters a daycare or preschool environment, as she realises that she needs to have certain skills for when that comforting person is not physically present to help; the individual child’s degree of reactivity – greater distress will inhibit the ability and effort to self-soothe, as this can only start to happen at lower levels of distress; presence of older siblings, as older siblings often model things for their younger siblings unintentionally and so younger siblings have often had more modeling experience than older siblings; and more.

How can I best respond?

Sometimes, the frustration a parent feels in these moments overrides everything. Feeling hurt and hopeless can lead to anger and resentment or simply giving up, yet none of these responses actually help our children in this moment (or you, the parent, for that matter). Hopefully, when we can realise that our child is attempting a new skill – like tying a shoe or getting dressed on one’s own – we can approach it with the same level-headedness and responsiveness that we would these other developing skills.