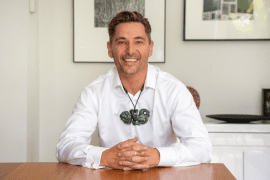

By Geordie Bull

Years ago, I remember receiving judgement from well-meaning relatives about the fact that my two-year-old son still had a dummy.

“It will affect his speech and mess up his teeth,” they said. “He won’t learn to express himself.” Knowing this was true, I harshly criticised myself for being too weak to throw out his pacifier. But there was more to it than that.

Working harder than ever and still not doing enough

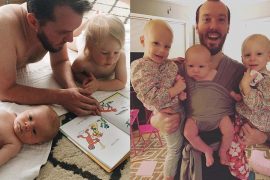

At the beginning of my parenting journey, I was a mother who completely subscribed to the ideals of attachment parenting and kept up with the latest child-development research. From the minute my kids woke up at 5am until they went to bed at 7.30pm, my day was spent running between them in an attempt to meet their ‘needs’ for attention, snacks, a playmate and comfort. Giving the pacifier to my son (who stopped day-napping at 18-months) was the only way I could complete a basic level of housework, go to the toilet or shower in peace.

At the time, I was incredulous that anyone could pick out the one area where I was failing to support my child’s optimal development whilst I was clearly drowning in anxiety, exhaustion and unhappiness.

But without a clear understanding of what I was experiencing, I made sense of it by assuming that there was something inherently wrong with me and that other mothers must be doing better.

The effect of intensive mothering ideology

Many years and conversations later, I learned that this wasn’t the case. As I gathered the courage to speak about how I was feeling with other mothers, they often echoed my sentiments in private.

I also discovered something that helped me piece together the reasons why so many mothers were working incredibly hard only to constantly feel like they were coming up short: intensive mothering ideology. This term was coined in the 1960s by an American sociologist named Sharon Hays to describe the dominant western cultural approach to motherhood as “child-centered, expert-guided, emotionally absorbing, labor-intensive and financially expensive”.

This discovery made me realise that mothering was never meant to be this hard.

It isn’t our children who demand that mothers should be able to perfectly cater to the many expert-defined ‘needs’ of their children, but the messages we’ve absorbed about what it means to be a ‘good mother’.

While I still believe that most of the expert advice I read was beneficial to children, all of it failed to consider a mother’s individual circumstances and the level of support around her.

Nothing in the attachment parenting literature that I’d consumed warned me that neglecting my own basic needs and emotions to co-sleep, baby-wear and remain hyper-responsive to every display of emotion would lead to exhaustion, overwhelm and anxiety – which in turn led to me being impatient and unkind with my children.

None of the experts informed me that the task of raising a child optimally was never meant to be shouldered by one person, but a community of loving people who all valued the care of both mothers and children.