By Adrienne Mead

I’m a parent with anxiety.

I’m neither defined by my anxiety nor ashamed of it. It’s just part of my journey. My children’s health, happiness, and well-being is the hook on which much of my anxiety hangs. Is she happy? Is this normal? Am I making the right choice for her? I feel like there’s a certain affectionate expectation of the harried, crazed mom. There she is, in her yoga pants and messy bun and extra-large coffee and her mini-van, shuttling the kids to their activities. It’s a familiar caricature; her neurosis is funny and relatable. But my challenges feel less cute. No one wants to identify with the mom who lays awake at night, a knot in her belly, obsessing over safety and milestones.

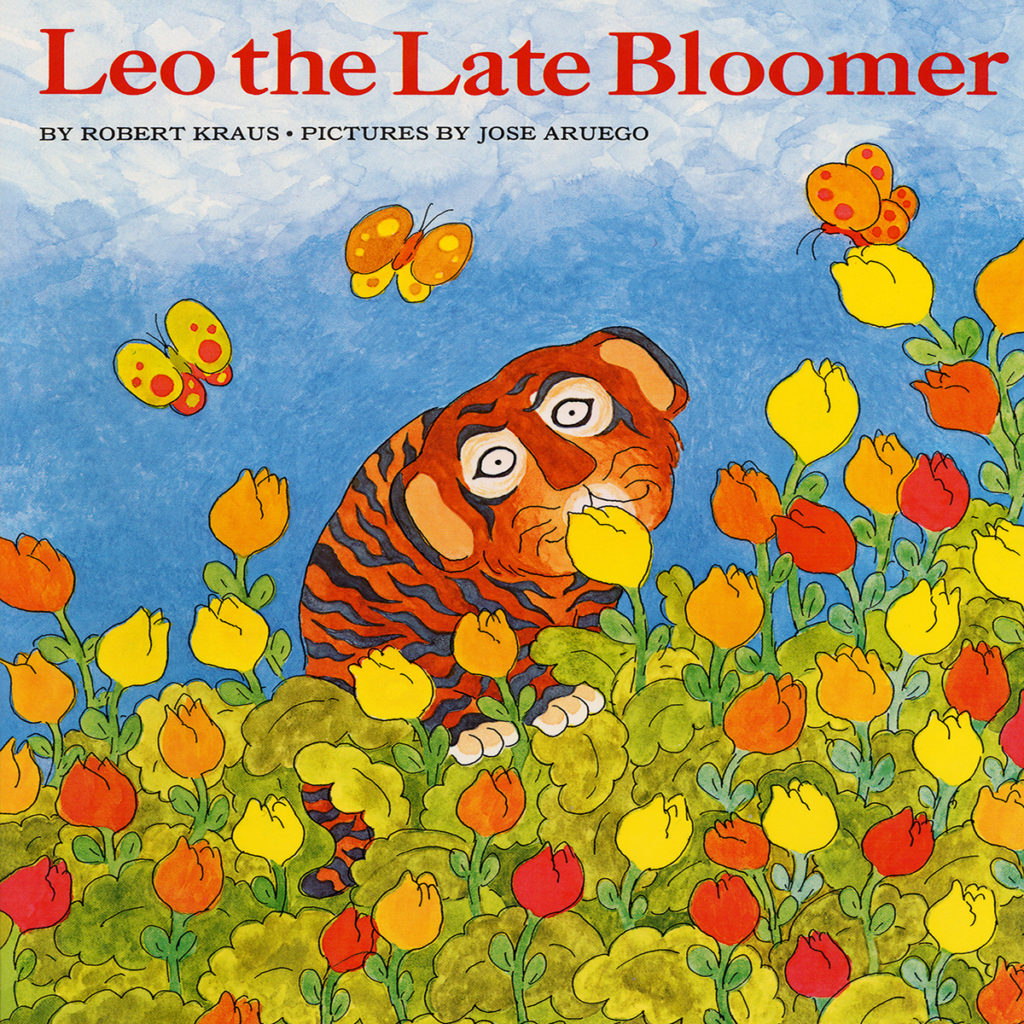

Have you read Leo, the Late Bloomer by Robert Kraus? If not, I can’t recommend it highly enough. In it, our hero, Leo, just isn’t on the same developmental path as his peers.

Leo’s father, probably the tiger to whom I relate the most in the world, is troubled by this. Leo’s mother reassures him that Leo will bloom in his own good time and that “a watched bloomer never blooms.”

It is only when Leo’s father turns away to watch television (as tigers do), that Leo finally comes into his own. I sometimes enjoy rereading “Leo” when my wheels are spinning particularly fast. A hovering parent, tiger or human, does nothing to help a bloomer of any variety.

My children attend the school where I teach, and it is all too easy to be a regular (and probably annoying) presence in the doorway of their classrooms, peeking in to see “how they’re doing.” Taking a cue from Leo’s dad, I recently had the shocking idea that I, too, could simply turn away for their benefit.

At the neighborhood pool this week, E, my newly five-year-old, decided that she wanted to find some friends to play with. I felt the same old rush of adrenaline. How would she join? Would she be accepted? Are the other kids kind? Every instinct in my body told me to beam in like a laser from the pool deck, hands on hips, supervising intently. I’m not sure why, but I decided to challenge that impulse this time.

“Look away,” I told myself. “Trust her. Let her learn from this.”

I felt self-conscious and awkward, sitting in the plastic pool chair and deliberately turning away from her, but I did it. About five minutes later, E approached me with a frown. “They said I’m too little to play their game.”

“Hmm,” I replied evenly. “Would you like to play with e [her little sister]? Or maybe find someone else to play with?”

She trotted off, back to the pool. My gaze followed her just long enough to see her approach another pair of girls, introduce herself, and listen to their names. Then I went back to my book.

Would E have had the confidence to try again if she noticed me hovering? I can’t say for sure. But maybe, just maybe, by my simply being a neutral presence – instead of an anxious lurker – she felt that I believed she could handle this on her own.